An Adoptee’s Perspective: What It’s Like to Be Adopted & How to Help

Insights and Ideas from an adult adoptee

As part of National Adoption Awareness Month, we are excited to bring you an adoptee’s perspective. Leah Sutterlin was gracious enough to give us her insights on what it’s like to be adopted. We trust her perspective will be as helpful and equipping for you as it was for us!

It’s easy to focus on adoptive parents—ways to support adoptive parents, whether to become an adoptive parent, how hard it is to be an adoptive parent, etc., etc.

But often, we forget to pause and ask ourselves, “What’s it like to be adopted?” Because, for these kids, the fact that they’re adopted is a big part of their identity. If you are an adoptive parent or thinking about becoming one (or you love a family that has grown through adoption), it’s critical to dig in and consider the adoptee’s experience.

Of course, to be clear, there’s not one single adoptee experience. However, across the wide range of stories, we can talk about some shared experiences.

I was adopted at the age of nine months and watched my parents go through the adoption process two more times with my younger sisters. I have spent years working with adoptees and their families through organizations such as Help One Child, the National Council For Adoption, and the Christian Alliance for Orphans. I have seen how adoption can strengthen families and introduce secure and loving relationships in a child’s life.

Why it’s important to talk about what it’s like to be adopted

Growing up, adoption was always part of my story. I would listen with great fascination as my parents told me about the long overseas trip to get me and all the new sights they visited: the Great Wall of China, the Temple of Heaven, and the Summer Palace.

We would also watch the video of when the nannies handed me to them for the first time, all bundled up for warmth in many layers. We would also celebrate my Adoption Day on March 28 with a favorite treat.

While I am grateful for my parents’ love and support, as I look back, it was not always easy to have adoption as part of my story. I faced many challenges with identity and belonging. It took both my parents’ constancy and my own faith journey to heal the brokenness caused by abandonment. Understanding what it’s like to be adopted can change the way you parent if this is part of your family’s story.

What surprised me about adoption

Even though I was adopted as a baby before I could talk or form memories, experiencing displacement during the first year of life caused a level of unspoken anxiety. For a long time, I used to wake up crying and wanted to fall asleep next to my mom or dad.

I faced insensitive comments in school as one of the few Asian children in a predominantly white environment. I remember hearing, “You should go back to where you came from,” or “You should be extra grateful that your parents adopted you.” This caused hurt and fear, reinforcing that I didn’t belong or that I was a burden.

Later in life, I saw my fear of abandonment and attachment issues manifest again in friendships and romantic relationships. I always worried about being left by a loved one, and I struggled when people drifted apart.

For example, in dating, I sometimes experienced a sense of panic before the commitment phase because I always felt like I was passing a test to earn approval. The prospect of someone saying “I love you” but leaving me really scared me. This issue caused a breakup in my relationship with my husband before we eventually reconnected and got engaged.

With the right tools and support (access to mental health resources and supportive community), I was able to go on to lead a fully satisfying life. I graduated from a top university, married into a wonderful family, and my compassion for children in need has led me to work at several adoption-related non-profits.

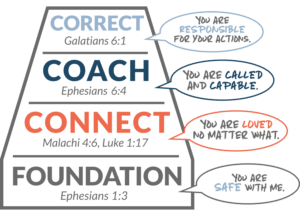

The Connected Families Framework is an effective tool for parents in any situation to understand the important messages their children need to thrive. Here, I will specifically adapt it to adoptive issues.

FOUNDATION: “I am safe in relationships – to question, grieve and struggle.”

As a child, I sometimes questioned why adoption was part of my story and if anyone truly wanted me. Given China’s one-child policy, I was left in a public location with no records or history of my biological family. Most of the questions around my adoption did not have known answers. It was often presumed my first parents did not have the means to care for me or wanted a boy to carry on the family name.

As a child and teen, I sometimes wrote letters to my birth mother—often filled with pain and anger. These expressed my frustration at not knowing where I came from and sadness that she was not around for special days of my life.

The loss of my first parents hit me most during adolescence. I was trying to form my own identity and felt misunderstood by my adoptive family because of our differences in interests and aptitudes. I questioned why God put me in a family that didn’t love academics, and I thought I might fit in better in a different family. My anger at this “mismatch” sometimes came out sideways in angry disrespect to my parents. “How did I end up in this family?!!”

I remember, in my anger, shouting hateful words at my parents and they would remind me, “We will always love you.” My parents were always willing to listen to my raw emotions but also remembered to point me to Christ for my sense of worth and security. Over time, I began to unpack my parents’ love for me and see it as a beautiful picture of unconditional love—love extended regardless of my merit and or how many times I pushed back or rebelled.

Fortunately, my parents verbalized how they viewed my adoption as a great blessing. They would always refer to my sisters and me as their daughters (not “their adopted daughters”) and talk about us with a sense of pride and gratitude. This created a sense of psychological safety, and I eventually was deeply grateful for having been placed in a family of faith.

There are many things I later wished I could have said to my parents at the time, but I struggled with the vocabulary to express my needs. Mostly, I wanted my parents to know that adoption was difficult for me at times and that feeling misunderstood was not a rejection of their efforts to love and guide me.

Prefer to listen?

Listen to Leah Sutterlin’s story on Ep. 204 of the Connected Families Podcast, “Being An Adoptee: What It’s Like to Be Adopted“

CONNECT: “I’m wanted. I belong!”

In many childhood settings, I struggled with a sense of “otherness.” I would have persistent thoughts, like, “Why do I feel out of place at extended family gatherings?” or “No one looks like me or truly understands me.” These same fears and insecurities can happen to anyone but were more pronounced for me because I was adopted by a family of a different ethnicity. Was I really wanted? Did I really belong?

I often wondered why my parents loved me. It seemed like they would have loved whichever baby they were given. I wanted to feel uniquely chosen. They always would tell me that they loved me because of their choice to love me and because God had given me specially to them.

This reminds me of Ephesians 1:4-6, “For he chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight. In love he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ, in accordance with his pleasure and will— to the praise of his glorious grace, which he has freely given us in the One he loves.”

My parents mirrored Christ’s love for me—patient, persistent, and covenantal—and delighted at my adoption into their family!

“For he chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight. In love he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ, in accordance with his pleasure and will— to the praise of his glorious grace, which he has freely given us in the One he loves.” Ephesians 1:4-6

Love is subject to change when it is given because of a person’s characteristics or actions. When love is given because of commitment, it builds trust in the character of the giver and can truly be transformational.

COACH: “I can be my own person.”

It can be hard to lose the biological connection of being raised in your first family, where significant aspects of your identity are predetermined. I often felt different from my parents and didn’t fit in with many of my peers. I had to navigate growing up Chinese in a very ethnically homogenous town and applying to the Ivy League with parents who had never attended college.

While it was not feasible for my parents to move to a more ethnically diverse city, they did help me stay in touch with the group of children adopted from China on the same trip as me. We joined in various reunion dinners and meetups. Later they helped me connect with Chinese exchange students who attended a local university. This was all extremely helpful in defining “who I was.”

I appreciated that my parents encouraged me to explore my interests and talents. I tried many sports, musical instruments, types of art and creative expression as a child. I learned that while I would never be a star athlete, I really loved writing, reading, and academics. This encouragement to explore communicated their value of the unique way I was created and that I belonged in their family just as I was… but that wasn’t always easy to fully embrace.

Because my parents didn’t have experience with many aspects of higher education, I found a mentor in church to guide me and serve as a reference for college and scholarship applications. This was extremely helpful, but the gap between how I was created and my parents’ interests and aptitudes added to my sense of “otherness.” I was just different, and it was harder to feel like I belonged in my family.

When a child looks around them and wonders, “Why don’t I belong here?” it feeds a deep insecurity. By encouraging them to see their differences not as a “mismatch” but as part of God’s unique design for their lives, they can grow in confidence and calling. You can help your child by asking questions like:

- “When do you feel most happy and alive?”

- “What activities relax or calm you?”

- “What things do you think about when you’re just relaxing?”

CORRECT: “I am responsible for my actions and my life.”

Even though I experienced trauma from early abandonment, I learned that I am still responsible for my own behavior.

My parents taught me that I need to treat them with respect. When I misbehaved, they enforced rules and consequences without shaming me, but they were also willing to listen to my fears and perspective.

By helping me assume accountability for my own weakness and sin, my parents showed me how to view myself through a biblical lens—as capable of change and in need of God’s grace. This helped me let go of a victim mentality.

Understanding what it’s like to be adopted will change how you parent

Based on the National Council For Adoption’s research of 1,247+ adoptees, here are 4 key ways to support your adopted child:

1. Take trauma-informed and mental health training

Every child is different and handles trauma and attachment differently.

Create the space for children to grieve at different times in their lives. Grieving is not a “one-and-done” experience. It might happen immediately after the placement, or when there’s a special occasion, like a birthday or holiday, or like me—when going through adolescence.

Children may also benefit from professional therapy in processing emotions related to their adoption. Some organizations offer communities for adoptees to connect with each other through support groups, social groups, camps, etc.

2. Connect your child to their birth culture

If adopting a child of a different ethnicity, try to find ways to connect them to their culture of origin. Children often benefit from seeing “mirrors” of themselves (children and adults who look like them). This may mean seeking out a church and community with more ethnic diversity and finding ways to integrate favorite traditional foods, customs, languages, and even dance groups.

3. Support your child’s questions about their biological family

Wondering about one’s origins is a natural and healthy exploration for children, and learning about one’s first family doesn’t need to be perceived as threatening. Though some children who have experienced adoption are not interested in or ready to explore their family of origin, research shows that most adoptees want support with searching for or connecting with their first family.

4. Speak positively about your child’s birth/first parents

Birth parents* have made a difficult but ultimately life-giving decision. With your support, the child can celebrate coming from two different families without feeling torn between the two.

For young children, the book Twice as Tight can be a helpful story that depicts thoughtful, unselfish love by a birth parent.

The term “birth parent” is evolving, and many birth parents now prefer the term “first parent” to designate their role and significance as one of an adopted person’s parents.

Adoption – a Biblical perspective

Romans 8:15 says, “For you did not receive a spirit that makes you a slave again to fear, but you received the Spirit of sonship [adoption]. And by him we cry, ‘Abba, Father.’”

Clearly adoption (both in the physical sense and in the spiritual sense) is a beautiful part of Scripture. Both those who adopt and those who are adopted receive a tremendous blessing, a privilege exemplified by our adoption into God’s family. By listening to your child and truly understanding their needs—either from their unique characteristics or from the trauma of adoption—you can help them thrive and realize their God-given potential in His Kingdom!

Looking for more information on adoption? We’ve got you covered! Check out these podcasts and blog posts:

- Why Safety is Crucial for Adoptive Families (and how it applies to ALL of us)

- My Misconceptions About Adoption—And, Well, All Parenting

- How Do I Support My Friend Who is Adopting?

- Adapting Christmas…for Children Who Joined Your Family Through Adoption

- Ep. 81: An Honest Conversation About Adoption

- Ep. 157: A Parenting Framework for Adoption and Fostering? Yes!

© 2024 Connected Families